Does Your Language Influence How You Think?

Would it be harder for people who speak a highly gendered language to create a more gender-neutral society?

Last November, I ran an episode on the myth that the Inuit language has a surprisingly large number of words for “snow.” I talked about how this myth is one example of a widely debunked idea called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, named after the linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. This hypothesis claims that the language you speak determines the way you think, or at least influences it. This hypothesis is also sometimes called linguistic relativity. Here’s one of the arguments against the idea of linguistic relativity that I summarized in that episode.

[M]ultiple languages have just one word that covers both the color blue and the color green. Researchers sometimes call these “grue” languages, “grue” being a portmanteau of “green” and “blue,” but people who speak these grue languages can still distinguish between blue and green. They recognize that they’re different colors even though they are covered by one word, in the same way that we recognize that light blue and dark blue are different colors even though we’d sometimes call them both just “blue.” There are some subtle differences-people who speak languages that distinguish between green and blue find it easier to accurately pick a bluish-green color they’ve seen earlier out of a group of swatches because it’s easier to remember something you have a distinct name for-but it’s not that they are better at recognizing or conceiving the difference between blue and green (1).

However, I recently read an article in “Smithsonian” magazine that seemed to challenge this view. It was about a court ruling in Germany saying it is unconstitutional for government institutions to assume that every person is either male or female. Any government form that people fill out now must have either a third gender to allow for people who identify as neither male nor female, or no gender question at all. The author of the article, Madhvi Ramani, argued that this ruling would be particularly troublesome for Germans, because German is a strongly gendered language (2). For example, you don’t just say you are a teacher. You are either a male teacher (der Lehrer) or a female teacher (die Lehrerin), and the author argued that this leads the German people to be especially partial to the idea of gender as a binary construct.

Would it be harder for people who speak a highly gendered language to create a more gender-neutral society?

So which is it? Can the language you speak influence your thoughts, or can’t it? The short answer is: Yes it can, but it’s not the kind of mind-blowing influence that people usually have in mind.

What kind of mind-blowing influence are we talking about that isn’t actually real? For my money, the best example is the science fiction movie “Arrival” from 2016. I won’t spoil it for those who haven’t seen it, but I can say this much: The protagonist, a linguist named Louise Banks, learns the language of some alien visitors to Earth, and doing so changes the way her mind works so much…that it’s a major plot point. In fact, it’s the basis of the big reveal near the end of the movie.

Linguistic Relativity and Color Names

Now, on to some aspects of language where people have done research to test the idea of linguistic relativity. Most of these examples come from “Language Files,” a textbook published by the Ohio State University Department of Linguistics, and a great TED talk by Lera Boroditsky (3), a linguist at UC San Diego who is the leading expert on linguistic relativism.

First, let’s talk about color names a little more. A famous study in 1969 by Brent Berlin and Paul Kay did not find evidence for linguistic relativity when it came to color names. Instead, they found that languages tended to follow similar patterns in what colors they had names for, and in the order in which they gained new color terms (4).

On the other hand, in favor of linguistic relativity are the facts about color terms that I mentioned earlier: People who speak languages that distinguish between green and blue find it easier than people who don’t to sort green and blue swatches into piles. There are similar results from the language Zuñi, which uses the same word for both yellow and orange (5).

Linguistic Relativity and Spatial Relationships

Another area in which people’s languages do seem to influence how they think is spatial relationships. As English speakers, we’re accustomed to using words such as “right,” “left,” “in front of,” and “behind” to indicate relationships, but once you think about it, it’s amazing how much confusion we put up with in order to make this system work. For example, in talking about theatrical plays, I still can’t remember where stage right and stage left are. Is it from the audience’s point of view, or the actors’? I know I can look up the answer, and I have, but I still forget.

Buy Now

Further, we say that a prisoner in a jail cell is behind bars. But now imagine that you’re that prisoner, and you’re facing a guard on the other side of the bars. From the guard’s point of view, you’re behind the bars. From your point of view, the guard is behind the bars. And what happens if you turn your back on the bars? Are you in front of them now?

Some languages, including some aboriginal Australian languages, do away with all that and instead use compass directions to express spatial relations. So instead of a right arm and a left arm, you might have an eastern arm and a western arm, if you were facing north or south. This eliminates the problem of having to specify “my left” or “your left,” but it also means you need to maintain a good mental map and always keep yourself oriented on it. And speakers of these languages can do this.

Some languages don’t have words for ‘left’ and ‘right.’ Instead, they use compass directions to identify positions.

If you asked me to point to the southeast, I’d need to think about it for a while, and ultimately might need to use a compass, depending on where I was. In contrast, a speaker of one of these Australian languages could do it right away. So does this mean that their language does influence their thought? Maybe, but it could also mean that in these people’s culture, knowing their directions is so important that they have incorporated it into the fabric of their language. In other words, their thoughts influenced their language.

Better support for linguistic relativity comes from an interesting experiment that had participants sit at a table with an arrow in front of them pointing north, to the person’s right, or south, to the person’s left. Let’s say it was north, to the right. Then the person had to turn 180 degrees to face another table, and this table had two arrows, one pointing north and one pointing south. That meant that the arrow pointing north now pointed to the person’s left, and the arrow pointing south pointed to the person’s right. The person was then asked to choose the arrow that pointed in the same direction as the first one. Would they interpret “the same” to mean pointing north, or to mean pointing to the right? Speakers of English consistently chose the arrow pointing to the right. However, speakers of a particular Mayan language that uses absolute directions consistently chose the arrow that pointed north! It seems like the quirks of each group’s language were influencing what they thought of as “the same.”

Linguistic Relativity and Gender

Next, there’s the topic of gender, which got me started on this path. When we’re talking about language, “gender” has a specialized meaning, which is all about how a language groups nouns and pronouns into a small set of classes based on commonalities. A language could potentially have dozens of these classes; for example, one language spoken in Papua New Guinea has at least 177 noun classes (6). When a language has only two or three classes, they’re more likely to be called genders. Depending on what nouns go in what classes, the language is said to have natural gender, grammatical gender, or both.

If a language has natural gender, its classes of nouns roughly correspond to classes of things in the real world. One way this could happen is that a language might have one class for nouns referring to living things, such as people, aardvarks, and snails; and another class for nouns that refer to nonliving things, such as rocks, houses, and oatmeal. A language like this is said to have two genders, animate and inanimate.

For example, Japanese differentiates between animate and inanimate nouns when choosing which existential verb to use. A sentence like “There’s a rock in my boot,” would use the verb “aru” for the inanimate rock, whereas a sentence like “There’s a snake in my boot,” would use the verb “iru” for the animate snake.

Another way for a language to have natural gender would be for it to have one class for nouns that refer to living male things, such as boys, fathers, and uncles; another class for nouns referring to living female things, such as girls, mothers, and aunts; and a third class for nouns referring to nonliving things, or living things that we don’t think of as being masculine or feminine. A language like this is said to have masculine, feminine, and neuter gender. English is this kind of language because we use pronouns such as “she” and “her” to refer to female things, “he” and “him” to refer to male things, and “it” to refer to almost everything else.

Now let’s suppose that a language has a masculine noun class that contains not only nouns referring to animate beings (e.g., men, husbands, and grandfathers), but also lots of other nouns referring to inanimate objects. Let’s also suppose it has a feminine noun class that contains not only nouns for animate beings (e.g., women, wives, and grandmothers), but also a lot of other nouns for inanimate objects. A language like this is said to have grammatical gender. Languages with grammatical gender will typically have different pronouns for their genders, too, so that instead of a word for “it,” speakers will use the equivalents of “he” or “she,” depending on the grammatical gender of the noun they’re referring to. They might also have different forms for adjectives that modify nouns with the different genders. They could even have different forms of the definite and indefinite articles for nouns of different genders. Some examples of languages like this are French, Spanish, and German. For example, in Spanish, the word for “key” uses a feminine article (“la llave”) and the word for “pocket” (where I often put my key) uses a masculine article (“el bolsillo”).

If an object has feminine gender in a language, people are more likely to describe it with stereotypically feminine adjectives.

As if it wasn’t complicated enough to talk about gender in language, it has also become complicated to talk about gender in human beings. In the last few decades, the word “gender” has become the preferred term for what used to be called “sex,” not only because the word “sex” can be embarrassingly ambiguous, but also because society has begun to recognize that classifications based on biological properties such as X and Y chromosomes and reproductive anatomy do not always correspond to a person’s psychological and emotional identity, which falls on a continuum from very masculine to very feminine.

But even if we accept gender as something on a continuum for human beings, gender in language is still the way it’s been for thousands of years, usually with just two or three. This disconnect sets up the question of whether a language’s system of grammatical gender can make it easier or harder for its speakers to think about social gender in non-binary terms. With this background in mind, let’s talk about Lera Boroditsky’s research. In a widely cited experiment, she had Spanish speakers and German speakers describe an object whose name in Spanish had one gender, and in German had another–for example, a key. Her team would show a key to the participants, without saying the Spanish or German word for it. Remember that the word for “key” in Spanish is feminine, and Boroditsky found that Spanish speakers tended to describe the key with words that fit many feminine stereotypes, such as the Spanish equivalents of “tiny” and “beautiful”—even without being reminded of the word’s gender by hearing it said aloud. On the other hand, the word for “key” in German is masculine, and German speakers tended to describe the key with words that fit male stereotypes, such as “useful,” “heavy,” and “strong.”

So what does that mean? It looks like a language’s gender system does influence its speakers in artificial experimental settings, but what happens in the real world?

To answer this question, a 2012 study by Jennifer L. Prewitt-Freilino, Andrew Caswell & Emmi K. Laakso (7) investigated more than 100 countries and their languages. They concluded that there tended to be less gender equality in countries whose primary language used grammatical gender than in countries whose primary language used natural gender or didn’t mark gender at all. Surprisingly, they found the most gender equality not in the countries whose languages didn’t use gender at all, but in the ones whose languages used natural gender. It works like this. In a genderless language, gender-neutral pronouns can be interpreted as referring to any gender, so it’s up to the listener to decide which gender is appropriate. And often, listeners are biased toward imagining a masculine gender. In contrast, if your language has gender-specific pronouns, such as “he” and “she,” then you have the option of using extra words to emphasize the existence or importance of different genders, which isn’t possible in genderless languages.

If German were Gender-Neutral

Ramani asks if a new German law will change the German language. My take is that it could over time, but only if German speakers are already willing to make such a change. So what would need to happen for the German language to be gender-neutral? We can get some insights from developments that have already happened in English.

In theory, one way would be to completely get rid of the notion that gender in language has anything to do with gender in real life. But realistically, that wouldn’t work. It would still be a fact that most words describing beings that are typically male in the real world fall into the same class of nouns, and similarly for nouns describing typically female beings. So what would be a more realistic way for this to play out?

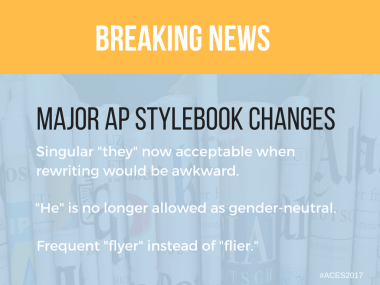

First, as Ramani observed, we’ll need pronouns that don’t refer to a person’s gender. In English, we’ve used the phrase “he or she.” In older stages of English, as well as in contemporary English, we also use the pronoun “they,” a usage that has been in the language for centuries, before being disparaged in usage manuals and grammar guides for the last century or two, and finally regaining respectability in the last few years. This could happen in German, too; in fact, they already use their pronoun for “they” as a polite form of the singular “you,” although they capitalize it when they do. Using it for a gender-indeterminate singular wouldn’t be much of a stretch.

Next, let’s think about the German definite and indefinite articles. If German speakers truly wanted to go gender-neutral, they’d probably create a word that’s recognizably like the existing words, but a little different. The German words for “the” are “der,” “die,” and “das”–Der Junge, the boy. Die Mutter, the mother. Das Glas, the glass–so maybe for a gender-neutral form they would just use something like “de.”

Again, something similar has also happened in English. English used to have different versions of the definite article for three genders, but during the Middle English period, the distinctions became less and less distinct, until we ended up with the gender-neutral, singular and plural form “the.” We talk about “the boy” and “the boys,” “the girl” and “the girls.” Whatever we’re talking about, we can use the word “the.” Something similar would probably happen with the German equivalents of “every,” “no,” and similar words; and adjectives in German, which also have different forms for masculine, feminine, and neuter.

What about German nouns referring to people? Ramani discusses some of German’s many noun pairs that are like the English “actor” and “actress,” with one word for males and one for females. Probably the most likely path to gender neutrality would be, once again, to do what English is doing. Some feminine forms, such as “actress,” are being quietly dropped, and the masculine forms are being used gender-neutrally. We discussed this in an episode about gendered nouns, #230. Others are being replaced by newer nouns that never had a gender distinction, such as “server” to replace both “waiter” and “waitress.”

Is any of this likely to happen? It depends on German speakers’ attitudes. If gender-neutrality in language is important to them, changes like these will happen as more and more individual people start to adopt them. Those who are opposed to it will vigorously resist the new words and usages; Ramani gives several real-life examples of this in her article. And children who grow up with the new forms will not find them unusual at all. All of this, I should add, is true for English, too.

Language and Cultural Attitudes

When considering experimental evidence like the kind we’ve discussed in this episode, it can be easy to overlook ways in which our language can fail to influence our thinking. For example, if you’ve lived long enough, you’ve probably noticed that in referring to emotionally charged subjects, such as different races or ethnicities, or disabilities, words that were once considered ordinary, or even scientific or polite, have become slurs, and have had to be replaced by new euphemisms. This may have even happened more than once in your lifetime. Linguists call this the euphemism treadmill, and it happens because the negative attitudes that people have about these ethnicities or disabilities attach themselves to the new words just like they did with the old words. The new words don’t change people’s attitudes; instead, the attitudes persist and make us have to replace the words every generation or two.

In his book “Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue,” John McWhorter, who now hosts Slate’s Lexicon Valley podcast, points out several ways in which linguistic relativity just doesn’t seem to operate, which proponents overlook (8). One of them is the euphemism treadmill. Another is English’s use of meaningless “do,” which we talked about in the episode “The Verb ‘Do’ Is Weirder than You Think.” In English, we use “do” to form negative sentences and questions; for example, we’d say, “Fenster didn’t move” instead of “Fenster not moved,” and “Did Fenster move?” instead of “Moved Fenster?” But this requirement to use “do” in negative sentences and questions didn’t exist in Old English. McWhorter observes that it would be silly to conclude that “English speakers have become especially alert to negativity and uncertainty, such that we have to stress verbs with ‘do’ in the relevant types of sentence.”

On the other hand, it would be wise to acknowledge that language can influence your thinking if you’re not paying attention. Advertisers and politicians have known this for ages, and use this knowledge in the metaphors they use. A particularly chilling example of language influencing people’s thoughts, and then their actions, is in the use of language that dehumanizes groups of people. Psychologists, sociologists, and historians are aware that acts of genocide usually begin with the use of language that compares the targeted group to predatory animals, vermin, or diseases. This makes it easier for people to overcome their moral repugnance to harming or killing fellow human beings, a lesson we should take special note of these days.

So, in summary, for many years the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was ridiculed, but ongoing research has found areas here and there, where some evidence does suggest that the inherent features of your language can change the way you think-but in small ways. If the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis were as obvious as some people think, euphemisms would be a lot more effective in changing people’s attitudes. On the other hand, if it were as false as many people argue it is, we would have much less to fear from insidious metaphors and dehumanizing language.

This segment was written by Neal Whitman, an independent PhD linguist who blogs at literalminded.wordpress.com. You can also find him on Twitter as @LiteralMinded.

References

-

Ludden, Patrick. “Fifty Shades of Grue: The Intimate Relationship between Language and Color Perception.”

-

Ramani, Madhvi. “Will a New Law Forever Change the German Language?” Visit more details here, link: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/will-new-law-forever-change-german-language-180968289/ [accessed Jul 15 2018]

-

Boroditsky, Lera. 2017. “How Language Shapes the Way We Think.” TED talk, Visit more details here, link: https://www.ted.com/talks/lera_boroditsky_how_language_shapes_the_way_we_think [Accessed June 25, 2018.]

-

Berlin, B. and Kay, P. 1969. Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evaluation, Berkeley: University of California Press. Cited in Language Files: Materials for an Introduction to Language and Linguistics, 11th edition. The Ohio State University Department of Linguistics.

-

Lenneberg, E. and Roberts, J. M. 1956. “The Language of Experience: A Study in Methodology.” International Journal of American Linguistics 22. Cited in Language Files: Materials for an Introduction to Language and Linguistics, 11th edition. The Ohio State University Department of Linguistics.

-

Surrey Morphology Group. Combining gender and classifiers in natural language. The University of Surrey. Visit more details here, link: https://www.smg.surrey.ac.uk/projects/gender-classifiers/?

-

Prewitt-Freilino, J. L., Caswell, C.A. & Laakso, E. K. The gendering of language: A comparison of gender equality in countries with gendered, natural gender, and genderless languages. Sex Roles (2012) 66:268–281. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257663669_The_Gendering_of_Language_A_Comparison_of_Gender_Equality_in_Countries_with_Gendered_Natural_Gender_and_Genderless_Languages. DOI 10.1007/s11199-011-0083-5 [accessed Jul 14 2018].

-

McWhorter, J. 2009. Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English, Avery.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.