Johannes Gutenberg: Language Rock Star

If you care about books, you should know the story of Johannes Gutenberg.

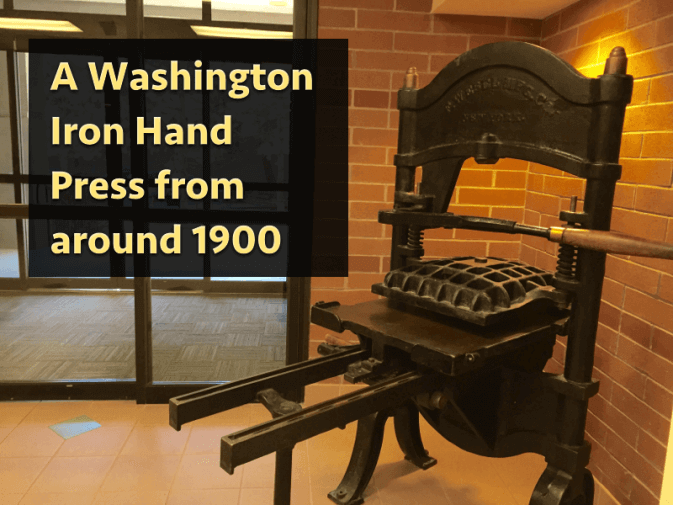

Photo Caption: This Washington Iron Hand Press was manufactured sometime around 1900 and currently sits in the lobby of the Reynolds School of Journalism at the University of Nevada. It is not a Gutenberg press—Gutenberg’s press was made from wood—but the design is similar. – Mignon Fogary

Although printing was first invented in China, Johannes Gutenberg invented the European moveable type printing press in Germany sometime between the late 1430s and early 1440s.

He is, of course, the namesake of his most famous book—the Gutenberg Bible, printed in 1452. The Gutenberg Bible, also called the 42-line Bible because each page has 42 lines of text, was one of the first books to be printed in mass production using movable type. Although mass production in this sense still means fewer than 200 identical copies, Gutenberg’s printing made the Bible more affordable than the handwritten copies available at the time, which could take more than a year to produce.

The Gutenberg Bible is the most famous book published by Gutenberg, but researchers believe he printed other books earlier, possibly Latin grammar schoolbooks.

Gutenberg’s printing process was revolutionary and heralded in the age of printed books and the Renaissance.

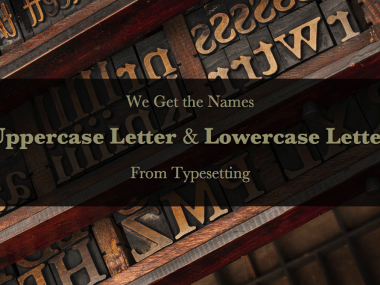

His first innovation was a way to efficiently cast individual letters out of metal. When using moveable type, printers have sets of individual metal letters and symbols that they place one at a time to make the template for printing each page. And, of course, everything has to be set in a mirror image of what the final page should look like, so it isn’t as straightforward as typing letter-by-letter on a typewriter or computer.

This process of creating books with moveable letters made editing printed books possible in a way that hadn’t been possible before. For example, in the earliest printings of the Gutenberg Bible, the first few pages were printed with only 40 lines of type. It was only in the later printings that pages had 42 lines of type. Gutenberg presumably reduced the spacing between lines so he could squeeze in more text and save paper.

Gutenberg had a good background to be crafting metal typesets because before he got interested in printing, he had worked with metal as a goldsmith.

Once the page of type is set, the printer inked it by hand, but the water-based inks of the time didn’t work well with the metal letters Gutenberg was making, so he also had to develop oily ink that would stick to his metal type.

Another one of Gutenberg’s flashes of insight was to adapt presses he saw other people using at the time. Gutenberg’s screw press was probably modeled after the presses growers used to make wine, olive oil, or paper. These are huge, heavy machines and printing each page was hard, physical work.

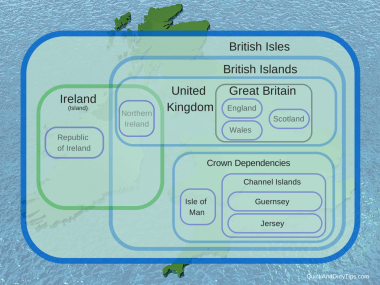

Because of Gutenberg, Germany was the early heart of the printing industry, and it was German printers who eventually spread the technology, migrating to all the European centers of industry to set up their own businesses. German printers set up the first print shops in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal. England is a notable exception, and I’ll talk more about England’s first printer—William Caxton—another time.

Interestingly, at the time, Gutenberg’s types were sometimes called “artificial scripts” and his goal at the time, and that of early printers to follow, was to have his books look as much as possible like books that had been produced by monks or scribes writing with ink and pen. That meant they had to have many more letters and symbols than we use in modern fonts to represent all the variations of handwritten scripts. For example, he used ligatures, which represent the way certain letters and symbols are written differently when they appear next to each other. Although it’s not always considered a traditional ligature, the ligature-like symbol you’re probably most familiar with would be the connected a and e you sometimes see in the British spelling of words such as encyclopaedia and archaeology.

Although printed books were still expensive, and early books such as the Gutenberg Bible were mostly bought by the church or universities, there was also a certain snobbery, with aristocrats considering printed books inferior to handwritten books. It seems that the middle class—people with enough disposable income to buy books, but not enough money to be immune to the high cost of handwritten books—were an important market for early printers.

One of the final things I found fascinating about Gutenberg is that he was a failed entrepreneur. To grow his business—perhaps to complete the Gutenberg Bible project—he used his print shop as collateral to borrow money from a wealthy lawyer named Johann Fust. Eventually the two men formed a partnership, but a few years after the Gutenberg Bible was printed, Fust took Gutenberg to court for misusing the funds and won. Gutenberg had to turn over his print shop and some of the books he had printed. Fust went on to print books of his own with Peter Schöffer, who had been Gutenburg’s assistant under the partnership and would eventually become Fust’s son-in-law and become an accomplished typographer and printer in his own right.

But Gutenberg didn’t give up. He went on to print more books in another shop until about 1460 when he may have gone blind.

Read about more language rock stars in The Grammar Devotional:

Print: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Powell’s

E-book: Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, Apple iBook

Note: This article was originally published February 4, 2012 and updated December 18, 2014.