Grammar Girl

Mignon Fogarty is the founder of the Quick and Dirty Tips network and creator of Grammar Girl, which has been named one of Writer's Digest's 101 best websites for writers multiple times. She is also an inductee in the Podcasting Hall of Fame.

Listen Now

More From Grammar Girl

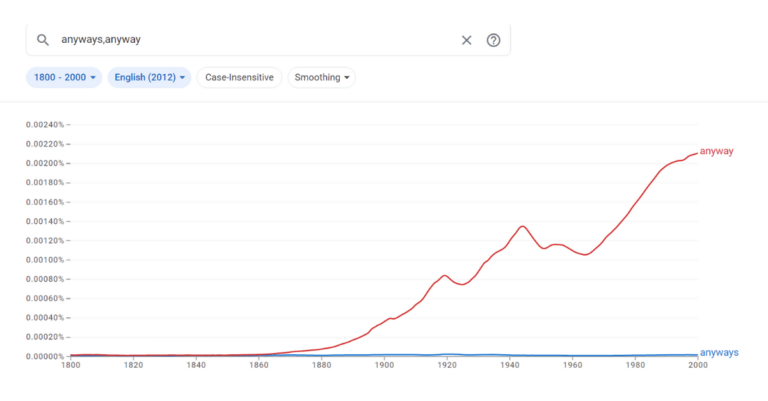

Anabell asked, “Is it correct or incorrect to say ‘anyways’ to someone? As in ‘Anyways, call me later!’ ‘Anyways&#...

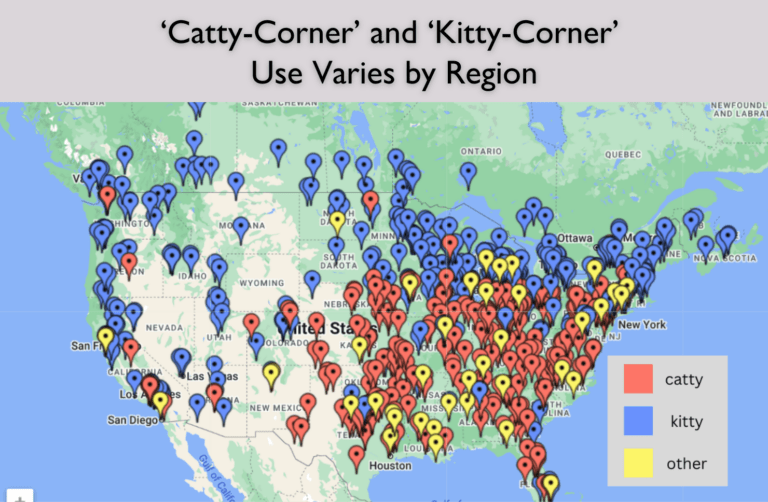

If you watched the recent “Curb your Enthusiasm” finale on HBO, you may have been delighted to see the old Americanism “catawampus&#...

A few weeks ago we talked about words that have changed meaning over time, like “nice” and “silly.” Another one of those words...

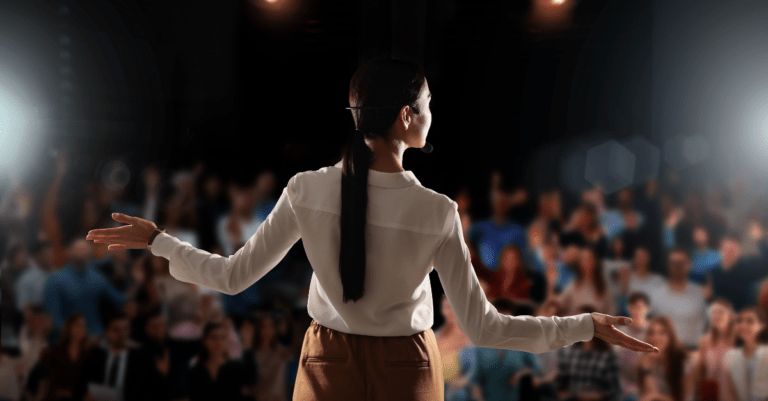

If you’re into sports, entertainment, politics, the news — you encounter commentators all the time. Heck, even the spelling bee has commentato...

This is a story about how a city got its curious name and what it means to be a namesake. The story begins in the late 1890s and takes place in rural ...

As we recently discussed in our tight writing segment in episode 940, it is important to have a strong BLUF (bottom line up front) in your writing and...

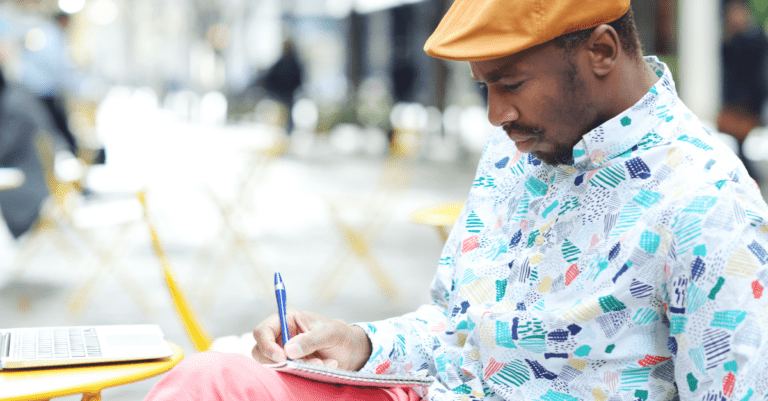

Some years ago I wrote a book called “The Sound on the Page: Style and Voice in Writing.” In it I tried to get at some of the elements — other ...

When autumn begins in the northern hemisphere, people often decorate their businesses and homes to get ready for Halloween. In 2021, the National Reta...

Sometimes people run afoul of standard grammar if they use the word “borrow” when they should have used “lend” or say “lend” when they sho...

A listener named Andrea once had the job title of “scriptwriter,” which spellcheck didn’t like. She said in her annual appraisal one...

About

Mignon Fogarty is the founder of the Quick and Dirty Tips network and creator of Grammar Girl, which has been named one of Writer's Digest's 101 best websites for writers multiple times. She is also an inductee in the Podcasting Hall of Fame.