Is ‘OK’ Okay?

I love “OK” so much I fight for it with my editors. Here’s why.

People often assume that it’s tough to be my copy editor, but the truth is that I’m pretty easygoing. I almost always accept my copy editors’ changes—except when they try to change “OK” to “okay.” Then I become a raving maniac. My usual wishy-washy countenance turns to granite.

One of my favorite stories is the origin of “OK,” and to me, “OK” is the purer form.

The origin of ‘OK’

“OK” was born in America in the 1830s. (So as an aside, you wouldn’t want to use “OK” in a novel set before the 1830s. That would be an anachronism).

Much like the text messaging abbreviations of today, “OK” was an abbreviation for a funny misspelling of “all correct”: “oll korrekt.” Journalists of the time seemed to have loads of fun making up these off-kilter, insidery abbreviations. Boston journalists are credited with “OK,” and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the “okay” spelling didn’t appear until 1895 in an Australian publication based in Sydney called “The Bulletin.” (So again, if you are writing a novel, you shouldn’t use the “okay” spelling before at least 1895.)

And in case you want even more spelling options, in 1919, H.L. Mencken wrote about Woodrow Wilson using the spelling “okeh,” but that one didn’t stick. Thank goodness!

Journalists in the 1830s came up with other odd abbreviations with similar origins too. They had “OW” for “oll wright” (a misspelling of “all right”) and “NS” for “nuff said,” but “OK” stuck while the others fell into obscurity because president Martin Van Buren, whose nickname was Old Kinderhook, because he was born in Kinderhook, NY, abbreviated “Old Kinderhook” into “OK” and adopted the campaign slogan “Vote for OK.” He called his campaign supporters the “OK Club,” and all that campaign publicity established “OK” in the American lexicon. It stuck.

‘OK’ and ‘okay’ are both OK

Today, the two spellings peacefully coexist: the Associated Press emphatically recommends the two-letter spelling, and the Chicago Manual of Style says both are fine, but the “O-K-A-Y” spelling looks more like a word. My publisher’s style is “O-K-A-Y,” but to honor the word’s origins, I insist on the “OK” spelling. So far, they’ve been kind enough to indulge me.

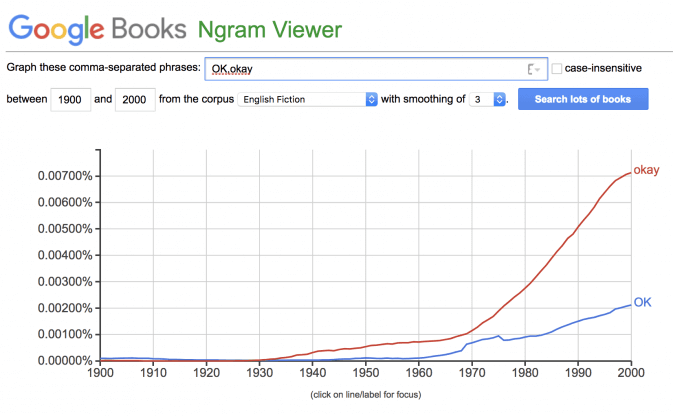

‘Okay’ dominates in fiction, but ‘OK’ wins overall

Because the “O-K-A-Y” spelling seems to be preferred by book publishers, though, that’s the dominant form in fiction, as you can see from the following Google Ngram search that is limited to English fiction:

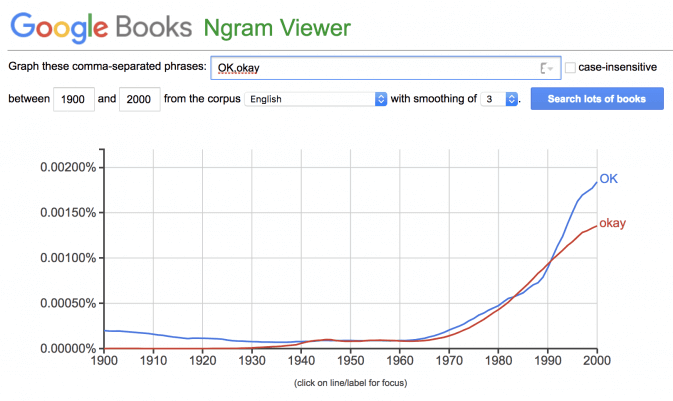

When the search is more broad, however, covering all English in Google Books, you can see that “OK” overtook “okay” in 1990, and continues to be used more often today.

You could speculate that the rise of “OK” was because text messaging caused people to favor the shorter spelling, which then eventually made its way into books, but text messaging didn’t really take off until about the year 2000, so the rise of the two-word spelling doesn’t quite match up with text messaging.

To sum up, you can usually use whichever spelling you prefer. They are both correct. If you have to follow AP style, you’ll use “OK,” but if not, you have some leeway, and you can use whichever one you like. I like “OK” because it’s more true to the origin and honors those wacky 19th century journalists.

‘OK’ and punctuation

For those of you who might be wondering, the Associated Press spells “OK” without periods, but some publications do use them. The New Yorker, for example, writes it as two letters with a period after each: “O.K.”

‘OK’: The entire story

Finally, some people say that “OK” is the most widely recognized English word in the world, and if you want to learn every detail of the story, the English and Journalism professor Allan Metcalf has written an entire 240-page book about it called “OK: The improbable story of America’s greatest word.” And for the record, note that he used the two-letter spelling.

[Note: The original version of this article said that Chicago style is “okay,” which is not correct.]

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.

You May Also Like…